Cartesian Forms (revision)

- Not covered since this is revision.

Factorisation of Polynomials

- A polynomial function is a sum of multiples of powers of a variable.

- e.g. .

- The degree or the order of a polynomial (7 in the example) is the highest power of the variable.

- In the case , you can think of this as , such it has the 0th degree.

- If a quadratic solution has solutions and , then the LHS admits a factorisation:

- i.e. solutions correspond to linear factors of the polynomials.

- this chapter extends this idea to higher degree polynomials (instead of just 2 degree ones lol)

Polynomial Arithmetic

- Polynomials can be added or subtracted by combining like terms and simplifying.

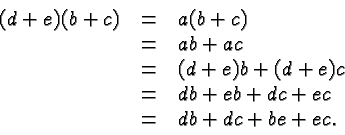

- Polynomials can be multiplied using the distributive law

- Gets a bit complicated for division. Can be divided using polynomial division.

- Division with integers.

- Consider a positive integer n (e.g. 100) and a strictly smaller positive integer p (e.g. 23)

- 100 not divisible by 23, so there is remainder r when 100 is divided by 23.

- Thus we can write

- q is the quotient = number of 23s in 100 :3

- r must be smaller than divisor (23), otherwise, if it is > 23, then u did division WRONG.

- In polynomial division, the remainder isn’t always SMALLER than the divisor (like integer division). HOWEVER, the order/degree is GUARANTEED to be smaller than the divisor of the polynomial.

- When a polynomial is divided by polynomial , the degree of the remainder will be strictly smaller than the degree of .

- Thus we can write

- E.g.

- this also works for integer division e.g.

- This can be rewritten as (wth is going on) OR

- e.g. (cannot lie idk what is going on)

- implications for algebraic fractions:

- proper algebraic fraction: (numerator degree is < denominator degree) - vice versa with improper algebraic fractions

- in certain later topics (partial fractions for integration) it will be necessary to rewrite improper algebraic fractions in terms of proper ones.

- We can use polynomial division to turn an improper algebraic fraction into a proper one!

- consider

&\frac{{x^2+3x+4}}{x+4} \text{ IMPROMPER RAGE} \\

&\implies\frac{{(x-1)(x+4)+8}}{x+4} \\

&=x-1+\frac{8}{x+4}\text{ proper yay! :D}

\end{align}$$

- sadler algebraic juggling ??? :P

- dividing by linear (specifically) polynomials

- if $P(x)$ and $(x-\alpha)$ are polynomials then $$P(x)=Q(x)(x-\alpha)+r$$

- i.e. for any polynomials $P(x)$ and $(x-\alpha)$, either $(x-\alpha)$ is a factor of $P(x)$, or there is a polynomial multiple of $(x-\alpha)$ that differs from $P(x)$ by a constant.

### The Remainder Theorem

> [!note] For a polynomial $P(x)$ and a number $\alpha$, the remainder when $P(x)$ is divided by $(x-\alpha)$ is $P(\alpha)$

>

e.g.

$$\begin{align}

&P(x)=2x^3+7x^2+10x+15 \\ \\

&P(x)=2x^3+7x^2+10x+15 \\

&P(-2)=2(-8)+7(4)+10(-2)+15 \\

&=7 \\ \\

&P(x)=2x^3+7x^2+10x+15 \\

&=(2x^2+3x+4)(x+2)+7

\end{align}$$

the remainder and the solution is the same!

#### Proof

$$\begin{align}

&\text{Let } r \text{ be the remainder when } P(x) \text{ is divided by } (x-\alpha) \text{. Then for some polynomial } Q(x), \\

&P(x)=Q(x)(x-\alpha)+r \\

&\text{Hence, } P(x) = Q(\alpha)(\alpha-\alpha)+r=r \text{ as required}

\end{align}$$

### The Factor Theorem

For a polynomial $P(x)$, $(x-\alpha)$ is a factor of $P(x)$ if and only if $P(\alpha)=0$

#### Proof

Suppose $x-\alpha$ is a factor of $P(x)$. Then the remainder when $P(x)$ is divided by $x-\alpha$ is 0, Hence, by the remainder theorem, $P(\alpha)=0$.

Conversely, suppose that $P(\alpha)=0$. Then the remainder when $P(x)$ is divided by $(x-\alpha)$ is 0. Hence $(x-\alpha)$ is a factor of $P(x)$.

if you multiply two polynomials, the degree of the product is equal to the sum of the degrees of the polynomials.

## Other stuff which is really useful to know

### Theorem (The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra)

- Every real polynomial equation of degree $n$ has exactly $n$ solutions (some of which may be repeated or complex).

- Or

- Every real polynomial $P(x)$ of degree $n\geq 1$ can be factorised as a product of $n$ linear factors $a(x-\alpha_{1})(x-\alpha_{2})\dots(x-\alpha _{n})$ where $a_{i}$ are the zeroes of $P(x)$.

E.g. $$\begin{align}

& x^4-4x^3-17x^2+110x-150 \\

& =(x+5)(x-3)(\times-(3+i))(x-(3-i))

\end{align}$$

- $\text{Suppose P(x) is a degree 7 polynomial. What is the maximum number of stationary points the grah of y=P(x) can have?}$

- derivative of degree 7 is degree 6(?) $\therefore$ Number of real distinct solutions = to 6, since real distinct solutions correlate to stationary points, P(x) has 6 stationary points.

### Theorem (Important! - part of the course)

- If $z$ is a complex solution to a polynomial equation (with real coefficients), then so is $\overline{z}$.

- This means that complex solutions always in conjugate pairs, so the total number of complex solutions (with non-zero imaginary part) is always even.

- It also means that the total number of linear factors involving complex numbers is even

- Conjugates comes as pairs, and you can ever have one solution without the conjugate pair

- **What important fact does this imply about the graphs of odd degree polynomials?**

- Any real polynomial equation of odd degree will have at least 1 real solutions

- odd degree: starts **up**/down and finishes **down**/up

- even degree: starts **up**/down and finishes **up**/down

### Theorem: Multiplicity of Factors

- Suppose that $(x-\alpha)^n$ is a factor of $P(x)$. Then...

- if $n$ is odd, the graph of $y=P(x)$ crosses the $x$-axis at $\alpha$

- if $n$ is even, the graph of $y=P(x)$ 'touches' but does not cross the $x$-axis at $\alpha$

- Consider $(x-2)^2(x+5)$

- both x = 2 and x = -5 is an x-axis

- HOWEVER, x = 2 is a parabolic shape, whilst x = -5

- not in the scope of the syllabus, but useful knowledge which helps you be more equipped with dealing with polynomial.

## Complex arithmetic in polar form

### Polar Form of Complex Numbers

- An exam question says:

- Evaluate $$(2+3i)\star(1-7i)$$

- given that $\star$ could be +, -, $\times$, $\div$, you can choose the sign you use.

- you would probably choose addition or subtractions, as it is easier to do than multiplication and division.

- polar form is friendly for multiplication and subtraction.

- reason for defining polar form is largely because it is more natural for raising powers, multiplication and division!

- you can thing of additions and subtractions as a vector.

- adding the complex number $1-7i$ translates the number by vector $\begin{pmatrix} 1\\-7 \end{pmatrix}$

- multiplying by pure imaginary number rotates complex number 90degrees anticlockwise.

- multiplication by a pure real number dilates complex number by a factor of the pure real number.

- geometric interpretation of complex number multiplication.

- when multiplying by a complex number $z$ the things determining the corresponding geometric transformations are:

- the distance $|z|$ from the origin (the 'magnitude' or '**modulus**')

- the angle $\theta$ from the positive real axis (the '**argument**')

- this suggests that a way of representing $z$ where $|z|$ and 0 are explicit could be useful!

- rewrite $z=a+bi$ so that $|z|$ and $\theta$ are explicit.

- **modulus** is determined using pythagorean theorem (a^2 + b^2 = c^2)

- $\cos \theta=\frac{a}{|z|}, \text{ so }a=|z|\cos \theta$

- $\sin \theta=\frac{b}{|z|}, \text{ so }b=|z|\sin \theta$

- $z=|z|\cos \theta+i|z|\sin \theta$ (i is put on left hand side to avoid confusion)

- $z=|z|(\cos \theta+i\sin \theta)$

$$\begin{align}

& \text{e.g. the complex number } \\

& \frac{5}{\sqrt{ 2 }}+\frac{5}{\sqrt{ 2 }}i \\

& \text{ has magnitude} \sqrt{ \frac{25}{2} +\frac{25}{2} }=5 \\

& \text{and} \\

& \text{argument} \frac{\pi}{4}. \\

& \text{so it can be written as } 5\left( \cos \frac{\pi}{4} +i\sin \frac{\pi}{4} \right) \\

& \text{aka } 5 cis\left( \frac{\pi}{4} \right)

\end{align}$$

- geometric interpretation of complex number multiplication.

- write z = a + bi so that |z| and $\theta$ are explicit

### principal argument

- the angle between the vector for $z$ and the real axis has $-\pi<\theta\leq \pi$

## complex number (polar form) multiplication and division

- abbreviated notation is $cis\theta$ which stands for $\cos \theta, i\sin \theta$

- multiplication by a complex number:

- $rcis\theta \times 3cis\left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right)=3rcis\left( \theta+\frac{\pi}{2} \right)$

- number is dilated by 3 and rotated by $\frac{\pi}{2}$

- in general $r_{1}cis\alpha \times r_{2}cis\beta=r_{1}r_{2}cis(\alpha+\beta)$

- be careful when adding the angle so it is within the principal argument!

### proof

$$\begin{align} \\

& \text{Claim:} \\

& \text{if }r_{1}cis\alpha \text{ and } r_{2}cis\beta \text{ are complex numbers, then} \\

&r_{1}cis\alpha \times r_{2}cis\beta=r_{1}r_{2}cis(\alpha+\beta) \\ \\

& \text{Proof:} \\

LHS &= r_{1}cis\alpha+r_{2}cis\beta \\

&= r_{1}r_{2}[(\cos\alpha i\sin \beta)(\cos\beta+i\sin \beta)] \\

&= r_{1}r_{2}[\cos\alpha \cos\beta+i\cos\alpha \sin\beta+i\sin\alpha \cos\beta+1^2\sin \alpha \sin\beta] \\

& = r_{1}r_{2}[\cos(\alpha+\beta)+i\sin(\alpha+\beta)] \\

&=r_{1}r_{2}cis(\alpha+\beta) \\

&=RHS \\

&&QED

\end{align}

Regions in the Complex Plane

this is usually the topic with the hardest exam questions - dr pearce

set notations

- for real numbers

- all values of x: such that ____ <- these conditions are true

- transfer these concepts to the world of complex numbers.

- for complex numbers

-

- wow this is a circle!

- some people call this the locus (of |z| = 4)

- <- now we replace = with leq sign!

- by convention we just shade the circle in!

- anything with modulus less than or equal to 4.

- this can also involve the argument, rather than the modulus:

- note that 0+0i is excluded from the set because its argument is undefined!

- sometimes the region represented by a set isn’t obvious.

-

&\text{Let } z=x+yi \\

&Then |x+yi+8| = |x+yi-4i| \\

&\sqrt{ (x+8)^2+y^2 }=\sqrt{ x^2 + (y-4)^2 } \\

&(x+8)^2+y^2=x^2+(y-4)^2 \\

&x^2+16x+64+y^2=x^2+y^2-8y+16 \\

&16x+64=-8y+16 \\

&y=-2x-6 \\

&\text{Hence, it is a straight line with a y-intercept of -6 and gradient of -2.}

\end{align}$$

- Alternatively, observe that $|z-a|$ is the distance between the complex numbers $z$ and $a$

-

![[notes/images/Pasted image 20231120092819.png|400]]

## nth roots of 1

- in the real world:

- $x^2=1$ solutions: $x=1$ or $x=-1$ (**2 real solutions** - 2 square roots of 1)

- $x^3=1$ solutions: $x=1$ (**1 real solution** - 1 cube roots of 1)

- $x^4=1$ solutions: $x=1$ or $x=-1$ (**2 real solutions** - 2 4th roots of 1)

- etc... alternating

- however, $x^4$ has 4 solutions (1, -1, i, -i)

- you can solve this by factorising:

$$\begin{align}

&x^4-1=0 \\

&(x^2)^2-1^2=0 \\

&(x^2+1)(x^2-1)=0 \\

&(x^2+1)(x+1)(x-1)=0 \\

&(x-i)(x+i)(x+1)(x-1) \\

\implies &x=\pm 1 \text{ or } \pm i

\end{align}$$

- consider $x^3$

$$\begin{align}

& x^3=1 \\

& x^3-1=0 \\

& \text{since we know x=1 is already a solution, divide everythign by x-1} \\

& (x-1)(x^2-x+1)=0 \\

& \text{use quadratic formula to solve for x} \\

& x = \frac{1\pm\sqrt{ 3 }}{2},1

\end{align}$$

- theorem: including complex numbers,, there are $n$ $n$th roots of 1. They have modulus 1 and are spaced at angular intervals of $\frac{2\pi}{n}$

- more general theorem: given a non-zero complex number $z$, the total number of $n$th roots of $z$ (including complex roots) is $n$.

- the roots all have same modulus, and are spaced at angular intervals of $\frac{2\pi}{n}$; i.e. they form the vertices of a regular $n$-gon

## powers of complex numbers (demoivres theorem)

- suppose we have $-3+4i$

- we can use binomial theorem, but that is BAD, use POLAR FORM for it.

- $r_{1}cis\theta \times r_{2} cis \theta_{2}=r_{1}r_{2}cis(\theta_{1}+\theta_{2})$

- for any positive integer $n$:

- $(rcis\theta)^n=r^ncis(n\times\theta)$

- this leads to very important mathematical theorem: demoirves theorem

### finding $n$th roots of a complex number

- find three cube roots of complex number

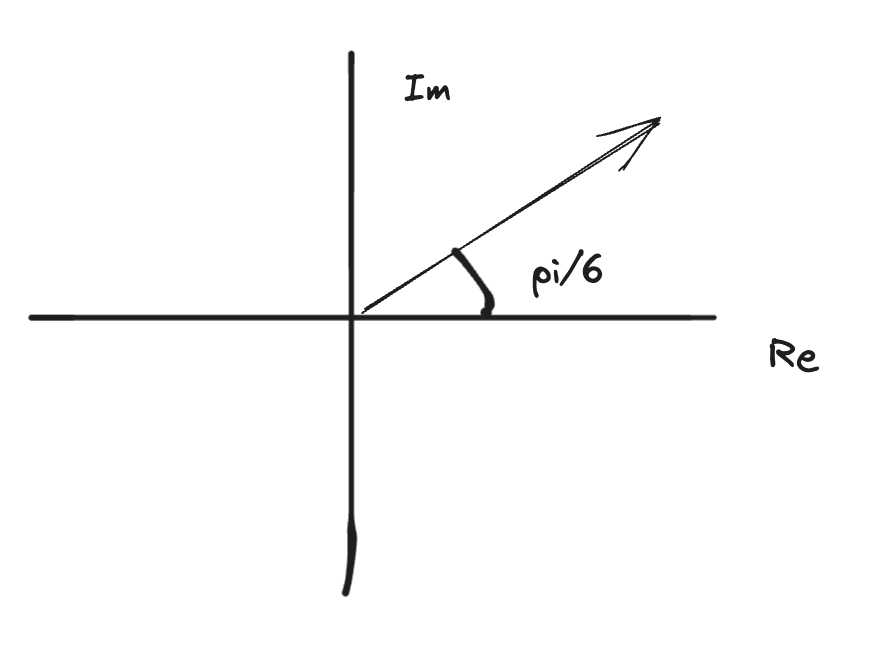

- $z=8cis\left( \frac{\pi}{6} \right)$

- need to find all solutions to

- $x^3=8cis \frac{\pi}{6}$

- $x=\left( 8 cis \frac{\pi}{6} \right)^\left( \frac{1}{3)} \right)$

- $x=2cis \frac{\pi}{18}$

- but that is only 1 solution :p

- $8cis \frac{\pi}{6} - 8cis (\frac{\pi}{6} + k 2 \pi)$ infinitely many ways of representing the argument!